EXHIBITION GUIDE

The four Martyrs of Lübeck

Eduard Müller

Johannes Prassek

Hermann Lange

Karl Friedrich Stellbrink

executed on 10 November 1943

WELCOME!

On 10 November 1943 four clergymen from Lübeck, the Protestant pastor Karl Friedrich Stellbrink and the Catholic priests Hermann Lange, Eduard Müller and Johannes Prassek, were executed by guillotine. The National Socialist People’s Court had condemned them to death in summer 1943. Since 2013 the Memorial to the Lübeck Martyrs has provided information about their lives and the sacrifice made by these men.

HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE

All the exhibition panels on the ground floor and basement are depicted and translated on the following pages. The guide thus enables you to move through the exhibition step by step. The monitors on the righthand site contain more information for you. Please use the touchpads beneath the screens to navigate and select the areas that interest you.

In the entrance, which is reached via the church, visitors can see a large crucifix that belonged to Hermann Lange. Displays on the wall to the church present the events involving the Lübeck Martyrs (beige section of the panels) in the context of their time and history (grey section). The room is illuminated by a row of windows opposite, which feature a large, 17-part printed work by the artist Julia Siegmund on the life and death of the Lübeck Martyrs. Between the windows there are four pillars with large portraits of the four martyrs. Monitors and headphones on the back provide additional audiovisual information about their biographies.

A staircase at the end of the room (there is also a lift) leads down to the former coal bunker in the cellar, where panels tell the story of the lay people and the parish housekeeper who were arrested along with the clerics. On the right is the history of their beatification. Straight ahead, a door leads to the memorial treasury, while the passage on the left goes to the crypt. It is intended as a place of remembrance, quiet and prayer.

The Lübeck Martyrs

On 10 November 1943 four clergymen were executed by the guillotine in a prison in Hamburg. The three Catholic priests Hermann Lange, Eduard Müller and Johannes Prassek worked at the Sacred Heart Church, and the Protestant pastor Karl Friedrich Stellbrink at the Luther Church in Lübeck, before they were arrested in 1942 and sentenced to death in 1943 after trial by the People’s Court in Lübeck.

Who were these four men who came to Lübeck in 1934 and 1939/40 respectively? Why did they collide with the National Socialist dictatorship and were subsequently

murdered? And why as a group have they been venerated since 1943 as the four Lübeck Martyrs, with the three Catholic priests beatified in 2011?

Background: from imperial monarchy to National Socialism

The four men were born in the German imperial monarchy, in a period marked by nationalism, militarism and anti-semitism. After defeat in the First World War in 1918 there was a revolution in Germany, which gave rise to a democracy: the Weimar Republic. It comes under great pressure from the outset, however, and is opposed by such different forces as communists and supporters of the imperial monarchy. The German population suffers great hardship following the hyperinflation of 1923. This and other problems are said to be the fault of the young democracy, although in fact the imperial monarchy is responsible. Confidence dwindles in the new form of government. Deference and a belief in authority still come naturally to many people. For this reason, a democratic mentality never takes hold in a majority of the population.

From 1930 onwards an extreme right-wing party, the National Socialists, is able to exploit people’s dissatisfaction and attract more and more voters, not least as a result of the global depression that begins in 1929. Adolf Hitler is appointed Chancellor on 30 January 1933 and the stage is set for the National Socialist dictatorship.

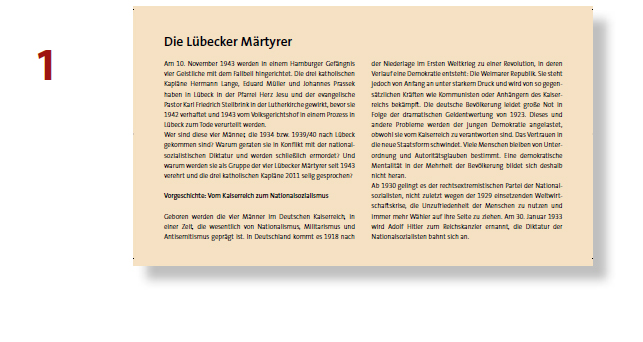

Lübeck 1933 – 1938

As everywhere in Schleswig-Holstein, flags with swastikas and men in uniform dominate the streets of Lübeck. The new system’s aggressive ideology is manifested among other things in the boycott of Jewish shops on 1 April 1933 and the burning of what is called “un-German” literature at the Buniamshof sports stadium on 26 May 1933. The director of the St. Annen- Museum, Carl Georg Heise, is dismissed because the Expressionist art he particularly supports is decried as “degenerate”.

Political opponents of the National Socialists are hounded, like Julius Leber, a member of parliament for the Social Democratic Party. For the first time in many years the Catholic parish of the Sacred Heart did celebrate the feast of Corpus Christi with a procession, but as a minority church it is increasingly exposed to interference from the dictatorship, and Catholic schools are shut by decree.

The new Protestant bishop Erwin Balzer was a hardline National Socialist and brought many doctrinaire pastors to Lübeck from 1933 onwards. In 1934 the Luther Church also gets a new pastor, Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, who has a very nationalistic, anti-semitic and anti-catholic attitude when he arrives. But from around 1936 he experiences a change of heart, which brings him into conflict with the dictatorship. He is expelled from the party as a result and also finds himself in an increasingly isolated position within the Protestant Church in Lübeck.

In Lübeck too, the war of aggression planned by the Nazis from the beginning led to the build-up of an extensive armaments industry. Several factories here produce arms and ammunition.

Captions

SA march past the Town Hall in Lübeck (6 March 1933)

Arms factory in Lübeck

Pastor Stellbrink and Bishop Balzer at the consecration of the new Luther Church in Lübeck

Herz Jesu-Kirche (Sacred Heart) in Lübeck

Nazi dictatorship and Kirchenkampf

After 30 January 1933 the National Socialists dismantled all democratic organisations in Germany within just a few months. It is above all this desire to control the lives of individuals right down to their most private affairs that reveals the totalitarian nature of the dictatorship.

In the long term the National Socialists aim to abolish the Christian churches altogether as public institutions. From 1933 the Protestant Church let itself be largely “aligned” or “consolidated” with the Nazi party in a process known as Gleichschaltung. This leads to a conflict, which in 1934 gives rise to the “Confessional Church” in protest against the co-option of religion by the state.

Before 1933 the Catholic Church generally set itself against National Socialist ideas and condemned parts of its party manifesto as heresy. Despite this, the Vatican signs a concordat with the Nazi state in July 1933 in order to avoid an open breach. Although it guarantees the independence of church organisations, the Nazi state increasingly restricts the freedom of Catholic schools, associations and newspapers over the following years. In a series of “morality trials” against priests, the National Socialists also try to drive a wedge between parishioners and the clergy. In 1937 Pope Pius XI criticises this policy in an encyclical written in German entitled “Mit brennender Sorge” (With burning concern), but it makes no difference.

Captions

Parliament without a function: the “consolidated” Reichstag in 1933

Ideological co-option of young people: “ Racial studies” as a school subject

Bonfire of “un-German” literature on 10 May 1933 in Berlin

Parishioners carrying flags to demonstrate church independence at a Catholic procession in Münster, 1936

Peaceful facade of dictatorship: Hitler at the Brandenburger Tor in Berlin for the Olympics in 1936

The papal nuncio Orsenigo with Hitler at the New Year’s reception in the Chancellery, Berlin

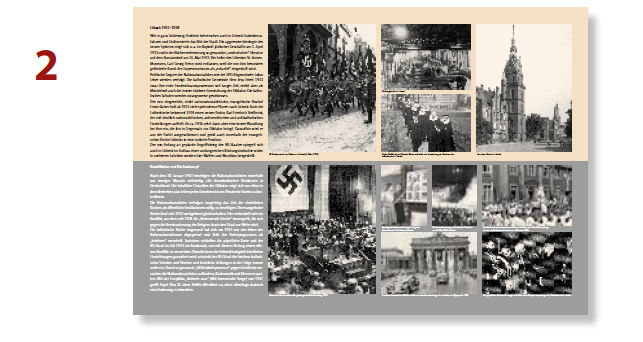

Pastoral care

In 1939 the Bishop of Osnabrück, Dr Wilhelm Berning, sends two young clerics to support Albert Bültel, the dean at the Sacred Heart Church in Lübeck: Johannes Prassek and Hermann Lange. They are followed in 1940 by Eduard Müller. All three studied in Münster and attended the seminary in Osnabrück. During this period they experienced the Nazi state’s campaign against the church and the efforts, especially by the Bishop of Münster, Clemens August, Count von Galen, to maintain its autonomy.

The three junior priests quickly become respected and popular figures in the parish of the Sacred Heart. As well as saying Mass, giving sermons and providing day-to-day pastoral care, they particular devote their time to young people. They organise discussion groups for children, adolescents and young adults.

Captions

Celebration of the Bishop’s 25th jubilee in Osnabrück in 1939, photographed by Eduard Müller: Bishop Clemens August, Count von Galen, and Bishop Dr Wilhelm Berning

Albert Bültel (*1887 †1954), Parish priest of the Sacred Heart and Dean of Lübeck deanary

Hermann Lange at the seminary in Osnabrück

Johannes Prassek at his ordination Mass

Eduard Müller in the presbytery garden at the Sacred Heart

War of aggression

By invading Poland on 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany starts a war of conquest, racial domination and annihilation. The Jewish population is mercilessly persecuted and murdered in all the occupied territories. In eastern Europe especially, the civil population is oppressed and abused in the name of a racist ideology. Millions of people from all over Europe are transported to Germany to work as forced labourers over the course of the war.

In contrast to 1914, the outbreak of war is not greeted with enthusiastic approval but rather with subdued acquiescence. Most of the population do not recognise the criminal nature of this war in 1939.

At the beginning of the war the leaders of the two main Christian churches express their support for the state in principle and call on the faithful to do their duty and to pray. However, some priests are much more critical than the bishops in conversation with their parishioners and attract the attention of the Gestapo, the secret police.

Caption

The Second World War begins with the invasion of Poland by the German army on 1 September 1939.

Critical attitude

Soon the discussion groups at the Sacred Heart no longer just revolve around religious instruction. The chaplains also talk with their parishioners about ethical and political matters or open up unusual dimensions of intellectual freedom for the young people, by looking at the art of the “degenerate” Ernst Barlach, for example. With these activities the priests resist the National Socialists’ attempt to recruit young people completely for the ideas of the dictatorship and to wrest them from the influence of their parents, school and church. It was precisely this struggle for the minds of young people that played a key role in Pastor Stellbrink’s change of heart.

The National Socialist state demanded the total identification of all citizens with the war. In this question too, the four Lübeck clerics came into conflict with the system, independently of one another. Pastor Stellbrink became increasingly critical of the war after 1939 and is given an official warning by the state. In the context of his discussion groups Hermann Lange says that according to his Christian beliefs, a Christian may not participate in an unjust war.

Captions

Hitler Youth in Lübeck

Eduard Müller working with young people to convert the coal bunker under the Church of the Sacred Heart into a youth club

St. Catherine’s Church in Lübeck with three sculptures made by Ernst Barlach in 1929 –1932, which were only installed in 1947, because the artist’s work was banned in the Nazi period

Military advances

After occupying Poland, German continues its invasion of western Europe in 1940. The rapid capitulation of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, but especially of France, puts Hitler at the height of his power. German failure in the Battle of Britain in late summer 1940 prevents an invasion of the United Kingdom, however.

The series of victories results in an unprecedented wave of support for Hitler’s policies on the part of the German population at large.

This general jingoism and euphoria makes it even more difficult for the few groups prepared to countenance resistance – in organised labour, for example, or nationalist-conservative military and aristocratic circles – to remove Hitler and the National Socialist system.

Captions

At the zenith of power: Hitler and army generals at the Eiffel Tower in Paris (June 1940)

Cheering crowds in Berlin after the French surrender

German aircraft during the Battle of Britain

United beneath the cross

In 1941 the Catholic priest Prassek and the Protestant pastor Stellbrink meet each other for the first time, although contacts between the two denominations are highly unusual at the time. Thereafter their common rejection of the anticlerical Nazi system and its crimes helps to forge the four Lübeck clerics into a group in which their doctrinal differences take a back seat. They exchange letters and even sermons critical of the system, keep themselves mutually informed about reports from foreign radio stations, and copy and distribute the sermons written by Bishop von Galen in summer 1941. In conversation, Father Prassek also criticises the treatment of Polish forced labourers in Lübeck and supports them secretly with pastoral care and practical assistance. The four of them accept that their activities could be punished severely by the totalitarian system.

Soon the group is being monitored by the secret state police, the Gestapo, which sends informants to take part in and report back on the discussion groups held in the presbytery of the Sacred Heart.

Captions

The presbytery of the Sacred Heart Church is the meeting place for religious talks, secret exchanges of information and the “last refuge of the free word” (Stephan H. Pfürtner)

Polish forced labourers in Lübeck: Tamara Warlamowa, Anna Krelman, Aniela Grzybowska

Reprints of critical sermons by Bishop von Galen, which were disseminated secretly and also dropped over Germany by allied bombers

Domestic battles

The German attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 marks a further extension of the war to the east, and an escalation of the Nazis’ criminal policies.

Within the German state the battle against the churches becomes ever more radical. Catholic monasteries and convents are systematically confiscated, the monks and nuns evicted and priests arrested. Any hint of criticism of the war or the state is prosecuted as “abetting the enemy”.

In this situation, three sermons by the Bishop of Münster, August Count von Galen, spark a controversy that goes well beyond the boundaries of the diocese itself. In them the bishop publicly criticises the killing of people with mental and physical disabilities and mental illnesses, which is practised systematically following the outbreak of the war. The popularity of von Galen and the widespread impact of his sermons mean the Nazi leaders do not dare to take action directly against the bishop.

Captions

Kasimierz Majdanski, Bishop of Szczecin-Kamin and a former prisoner at Dachau concentration camp, in the reconstruction of an original camp hut in 1989. Over 2,700 priests from both Christian churches and from some 20 countries are incarcerated at Dachau concentration camp, of whom more than 1,000 die.

“Gemeinnützige Krankentransport GmbH (“Charitable Ambulance GmbH”): these buses are used to kill sick and disabled people with injections and pills

Ideological pamphlets from the NSDAP, which represent “idolatry” and “paganism” for Bishop von Galen

Order with Hitler’s signature to murder mentally and physically disabled people

Clemens August Count von Galen (1878–1946), Bishop of Münster from 1933 to 1946, beatified on 9 October 2005

Indictment

In the night from 28 to 29 March 1942 (Palm Sunday) bombers from the British RAF attack Lübeck, destroying broad swathes of the city. A few days later Pastor Stellbrink is arrested, because in a sermon about the air raid he is said to have spoken of “divine judgement”, in the sense of punishment. By deliberately taking Stellbrink’s words out of context, the NS state now takes the opportunity to root out this source of resistance. In the following weeks the Catholic priests are arrested too. Whereas the Protestant church immediately disassociates itself from Stellbrink, the Catholic Bishop of Osnabrück, Wilhelm Berning, tries to get in touch with the prisoners, which he is only able to do after several months. The internees suffer from the inhumane conditions, especially their total isolation after their arrest. At the same time their surviving letters illustrate their unbroken trust in God and their certainty that they had acted correctly by following their conscience and defending the values of their faith and humanity.

Captions

Destruction of the street Parade after the air raid on 28- 29 March 1942

Lübeck-Lauerhof Men’s Prison

Lübeck-City Remand Prison

Police photos: Karl Friedrich Stellbrink is photographed on his arrest in 1942. The photos of the three priests from June 1943 clearly show the signs of 12 months’ imprisonment.

Radicalisation

At the Wannsee Conference held on 20 January 1942 in Berlin the definitive elimination of European Jewry is planned with bureaucratic precision and cold technicality. In the subsequent years of the war this genocide is put into effect to an inconceivable extent in the extermination camps.

The course of the war starts to turn in 1941/42 with military setbacks on the eastern front and the intervention of the USA.

Now the terrible impact of the war is becoming increasing tangible for the German civilian population too: Hundreds of thousands of German soldiers die far from home, allied bombing squadrons intensify their raids on German cities.

The targets of the bombing raids are not just industrial facilities and infrastructure, but also inner-city and residential areas. They are intended to shake people’s faith in Hitler and the “Ultimate Victory”.

Captions

“Selection” at the ramp of Auschwitz extermination camp

The Second World War claimed previously unimaginable numbers of lives.

Allied bombers over Germany

The air raids wipe out entire inner cities: destruction of the Town Hall in Lübeck

Martyrdom

In June 1943 the “trial” begins before the 2nd Senate of the People’s Court, which meets in Lübeck for the purpose. Its judgement is a foregone conclusion. All four clerics are sentenced to death for “broadcasting crimes”, “undermining military morale” and “treasonably abetting the enemy”. To avoid involving the formidable Bishop von Galen, what was previously considered the main charge of “disseminating von Galen’s sermons” is dropped from the indictment at Hitler’s personal initiative. Appeals for clemency, and the personal intervention of Bishop Berning and Stellbrink’s wife, have no effect, however. In its hatred for the churches the National Socialist system obviously intends to make an example of the clerics, in order to stifle domestic criticism about the conduct of the war.

In prison the clerics are preparing themselves for the end of their earthly lives. They go to their deaths unbroken, trusting in the love of God and with heads held high. Their farewell letters offer moving evidence that this was the case.

Starting at 6 p.m. on the evening of 10 November 1943 the four men are beheaded on the guillotine within a few minutes of each other.

Captions

Site of the “trial”: courtroom of Lübeck Law Court

Defence counsel: Dr Walther Böttcher, later President of the Schleswig-Holstein Parliament (1954–1959)

The judge: Dr Wilhelm Crohne

Extracts from the farewell letters dated 10 November 1943

Copy of the guillotine used to execute the convicts at the Holstenglacis prison in Hamburg

The beginning of the end

The surrender of the 6th German Army in Stalingrad in January 1943 is the decisive turning point in the war. German troops are subsequently pushed back on all fronts. The response of the German population was a mixture of shock and defiance, accompanied by increasing scepticism about the propaganda.

The National Socialists reacted to the military setback by further radicalising their policies: in a speech at Berlin Sports Palace on 18 February 1943 the Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels declares “total war”. This entails even more widespread persecution and punishment of people who offer any resistance or criticise the workings of the system. So, for example, on 22 February 1943 the students Hans and Sophie Scholl, along with Christoph Probst, all members of the resistance group the “White Rose”, were executed by guillotine.

Under its president, Roland Freisler, the People’s Court becomes a symbol of how the judiciary intensified the reign of terror by the dictatorship.

Captions

German soldiers on their way to prison after the surrender in Stalingrad

In his “Sports Palace Speech” (Berlin, 18 February 1943), the Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, tries to mobilise the German people for “total war” despite the military defeats.

Symbol of judicial terror: the People’s Court and its president, Roland Freisler

The Lübeck Martyrs

The National Socialists try to erase all traces and memories of the Lübeck clerics. For a long time they refuse to return the victims’ mortal remains to their families.

Most of the ten farewell letters that the four men wrote on 10 November 1943 to their families, the Bishop of Osnabrück and Father Bültel are not given to their intended recipients. For two letters in particular, from Hermann Lange and Johannes Prassek to Wilhelm Berning, the Bishop of Osnabrück, representatives of the perverted Nazi judiciary justify this internally with the fear “that the (...) letters could somehow get into the hands of unauthorised persons and (...) be used for propaganda detrimental to the interests of the state”.

Even after their murder, the National Socialists still obviously consider the Lübeck clerics to be a danger to the system, because Germany’s military situation is deteriorating on all fronts and dissatisfaction in the population is growing.

The liberation

Eighteen months later, Nazi Germany is finished. Military collapse is followed in 1944/45 by the complete occupation and liberation of Germany by the victorious Allied powers, Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union.

On 8 May 1945 the Second World War ends in Europe with Germany’s unconditional surrender. The result of the National Socialists’ megalomania and barbaric, racist ideology, its terror and its desire for destruction is more than 55 million dead – including more than six million Jews alone, murdered in the Holocaust. Europe lies in ruins. Millions of people lose their homes.

Lay people arrested too

Following the arrest of the four clerics, the Gestapo take eighteen more lay people into custody up to the autumn of 1942. Most of them participated in the discussion groups organised by the three Catholic priests in the Sacred Heart Church. Like the clerics, the prisoners are initially detained in the prison in the Castle Friary and at Lauerhof prison. They remain under arrest for almost a year, until their trial at the People’s Court.

The Gestapo wants to use statements from the lay people against the clerics. But this does not work, because no such statements can be extracted from any of the men. Solitary confinement, beatings and intimidating interrogations make no difference. Looking back, Stephan Pfürtner describes how demoralising the conditions in the prison were: “On the surface, it was days of endless monotony, but it was precisely that which tore open such chasms inside us. What do you do, when day after day goes past, you are sitting in a cell that measures about 8 feet by 8 feet, nothing to read, nothing to write with, no work, no one to talk to?” In Pfürtner’s case the interrogations by the Gestapo also focused on whether there was any connection to the students in the “White Rose” resistance group in Munich, which was not the case. The families of the parishioners arrested also come under considerable pressure: they are not only tormented by concern for their relatives, but are also harassed by the state. But at the same time the families in the Catholic parish do get support from neighbours and friends. When the prisoners have to build a shed for the Gestapo in Lübeck, although they are under guard, a lucky chance enables the women and children to see the men at least briefly. They take the opportunity to give them food and even hosts for holy communion.

At their trial before the People’s Court sixteen of the lay people are sentenced to short prison sentences and released directly, since their time on remand is offset against the sentence. They are deemed to have been “led astray” by the priests. Two of them, however, who are linked to the Sacred Heart in a professional capacity, are given longer prison sentences for “broadcasting crimes”: the treasurer Adolf Ehrtmann and the registry clerk Robert Köster. The latter is sentenced to one year in prison, where he remains until October 1944. He dies in 1946.

Adolf Ehrtmann is sentenced to five years hard labour and only released at the end of the war. As a local politician and Senator for Urban Planning, Ehrtmann plays a role in rebuilding Lübeck after the war.

The housekeeper Johanna Rechtien

The arrested priests received valuable support from their housekeeper, Johanna Rechtien (*1911 | †1991). She had taken care of the presbytery on Parade since 1933 and continued to work there throughout the war until the death of the parish priest Father Bültel in 1954.

When the three Catholic priests are arrested, Johanna Rechtien, whom Johannes Prassek addresses affectionately in a letter to her as “Aunty Hanna”, does their washing and repeatedly manages to bring basic everyday items into the prison for them, such as shaving equipment or warm jumpers. The writing materials and books that the housekeeper also gets for them are very important for the priests in their interminable solitary confinement. But Johanna Rechtien goes even further and takes considerable risks to hearten and comfort the prisoners. She manages to smuggle hosts and communion wine into their cells in the bundles of washing, so that the priests can celebrate Mass every day. For both the clerics and the lay people, one of the most painful aspects of their imprisonment was not being able to go to Mass and receive holy communion.

Johanna Rechtien did not worry about the religious denomination of the prisoners either. She also provided the same assistance to the Protestant pastor Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, as he wrote to his wife Hildegard in a letter from prison, asking her to send his daughters to thank the housekeeper on his behalf.

The Catholic priests use their housekeeper as a conduit for smuggling uncensored messages out of the prison. This enables them to be much more open about describing the conditions under which they were held.

Johanna Rechtien showed proof of exceptional courage in her support for the four imprisoned clerics, because she would have been arrested and condemned herself if the Gestapo had found out about what she was doing.

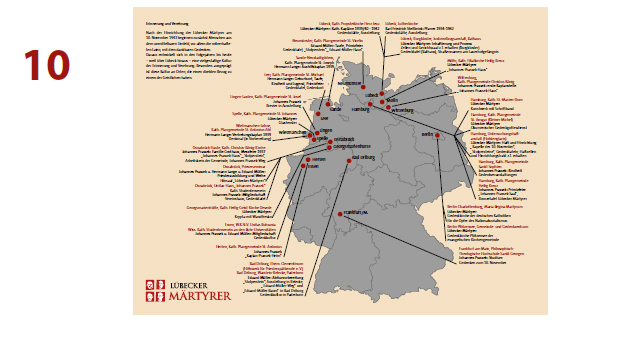

Commemoration and veneration

After the execution of the Lübeck Martyrs on 10 November 1943 it was people from their immediate environment, above all the lay people arrested with them, who first started to remember them with gratitude.

In the following years, and to this day, a multi-faceted culture of remembrance and veneration has grown up around them which goes far beyond the city of Lübeck. It is particularly strong in places that have a direct connection to one of the clerics.

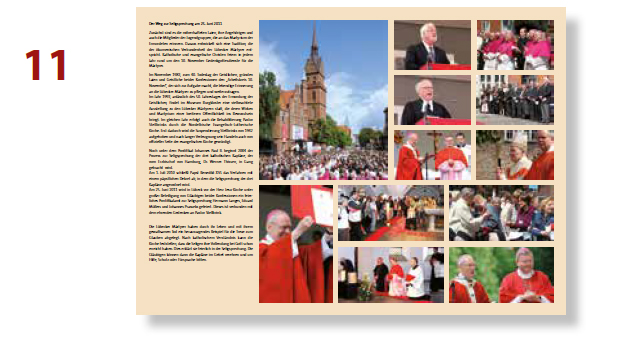

The path to beatification on 25 June 2011

At first it is the lay people arrested with them, their families and the members of the youth groups who commemorate the martyrdom of the murdered clerics. This develops into a tradition that coincides with the ecumenical solidarity between the Lübeck Martyrs. Catholic and Protestant Christians celebrate memorial services for the martyrs every year around the 10th of November.

In November 1983, to mark the 40th anniversary of their execution, lay people and clerics of both churches set up the “Working Group 10 November”, with the aim of keeping the memory of the Lübeck Martyrs alive and making their sacrifice more widely known.

In 1993, for the 50th anniversary of the clerics’ murder, the Castle Friary Museum hosts an acclaimed exhibition about the Lübeck Martyrs, which makes their work and martyrdom known to a wider public. In the same year Pastor Stellbrink was rehabilitated by the North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church. It was only this step which revoked Stellbrink’s suspension dating from 1942 and marked the official acknowledgement of his actions by the Protestant church after decades of denial. The process of beatifying the three Catholic priests begins in 2004, during the pontificate of John Paul II, at the initiative of Dr Werner Thissen, Archbishop of Hamburg.

On 1 July 2010 Pope Benedict XVI concludes the process with a papal decree announcing the beatification of the three priests.

On 25 June 2011 a Solemn Pontifical Mass is celebrated in front of the Sacred Heart Church in Lübeck before a large congregation of both denominations to celebrate the beatification of Hermann Lange, Eduard Müller and Johannes Prassek. It is combined with the solemn remembrance of Pastor Stellbrink.

By their life and their violent death the Lübeck Martyrs represent an outstanding example of devotion to their faith. According to Catholic doctrine, the Church can determine that the beati have already entered the Kingdom of God. This solemn declaration is the essence of their beatification. The faithful may then venerate the priests in their prayers and ask them to intercede on their behalf.